Last update on: 9:27 am July 9, 2024 by fashionabc

Impact of Textile And Clothes: Towards A Sustainable Fashion Industry In Europe

The fashion industry is an industry in constant growth. EU citizens buy around 6.4 million tonnes of new clothing every year – some 12.66kg per person, that means a 40% increase since 1996. However, more than 30 % of clothes in Europeans’ wardrobes have not been used for at least a year. Once discarded, over half the garments are not recycled, but end up in mixed household waste and are subsequently sent to incinerators or landfill. That leaves only half of those used clothes to be collected for reuse or recycling when they are no longer needed. Additionally, only 1 % are recycled into new clothes. The apparel sector is in need of a deep change, at all levels, to become a truly conscious and sustainable fashion industry. And here is how the European Union is trying to tackle the issue.

According to the paper, Environmental impact of the textile and clothing industry, about 5 % of household expenditure in the EU is spent on clothing and footwear, of which about 80 % is spent on clothes and 20 % on footwear. Likewise, the European Environment Agency (EEA) has recently stated that since 1996, the amount of clothes bought per person in the EU increased by 40%, driven by a fall in prices and the increased speed with which fashion is delivered to consumers.

This increase in consumption has been fostered by several trends, but two are the main drivers. Firstly, the fall in the price of garments in the last few decades. According to the same EEA report, between 1996 and 2012 the price of clothing increased by 3 %, but consumer prices in general rose by about 60 %. This meant that, relative to the EU consumer consumption basket, the price of clothing fell by 36 %. At the same time, the share of clothing in household consumption stayed largely the same: it was 5 % in 1995 and 4 % in 2017.

The second significant trend was the rise of fast fashion. Epitomised by the multinational retail chains, it relies on mass production, low prices and large volumes of sales. The business model is based on knocking off styles from high-end fashion shows and delivering them in a short time at cheap prices, typically using lower quality materials. Fast fashion constantly offers new styles to buy, as the average number of collections released by European apparel companies per year has gone from two in 2000 to five in 2011, with, for instance, Zara brand offering 24 new clothing collections each year, and H&M between 12 and 16. This has led to consumers to see cheap clothing items increasingly as perishable goods that are ‘nearly disposable’, and that are thrown away after wearing them only seven or eight times.

These two trends have been possible thanks to the relocation of the manufacturing process outside the European Union, often in countries with lower labour and environmental standards, and a complex global value chain. According to the European Commission, in 2015 the main exporters to the EU were China, Bangladesh, Turkey, India, Cambodia and Vietnam. Nevertheless, according to Euratex, the EU textile and clothing sector exported €48 billion worth of products in 2017, making the EU the second largest exporter in the world – the first being China. At the same time, the EU imported textile products worth €112 billion from third countries.

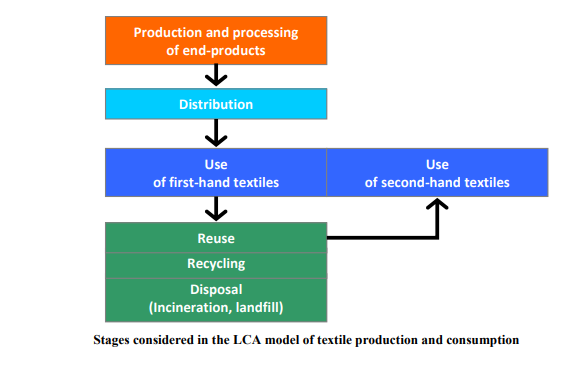

Stages considered in the LCA model of textile production and consumption

A Carbon Footprint Hard to Track Down

It is thought that clothing and apparel accounts for between 2 % and 10 % of the environmental impact of EU consumption. This impact is often felt in third countries, as most production takes place abroad. However, environmental impacts of EU consumption of textiles and clothing are difficult to estimate due to their diversity and the fact that they occur around the globe.

A 2006 Joint Research Centre (JRC) report estimated that while food and drink, transport and private housing account for 70 to 80 % of the environmental impact of EU consumption, clothing dominates the rest with a contribution of 2 to 10 %depending on the type of impact. A 2017 report by Global Fashion Agenda (GFA), estimated the EU’s environmental footprint caused by the consumption of textiles at 4 to 6 %. Going into more detail, the 2017 Pulse of the Fashion Industry report, put together by GFA and the Boston Consulting Group, estimated that in 2015, the global textiles and clothing industry was responsible for the consumption of 79 billion cubic metres of water, 1 715 million tons of CO2 emissions and 92 million tons of waste. It also estimated that by 2030, under a business-as-usual scenario, these numbers would increase by at least 50 %.

The production of raw materials, spinning them into fibres, weaving fabrics and dyeing require enormous amounts of water and chemicals, including pesticides for growing raw materials such as cotton.

Likewise, most textile raw materials and final products are imported into the EU, which means long delivery routes. However, according to the aforementioned Pulse of the Fashion Industry report, this stage accounts for only 2 % of the climate-change impacts of the industry, as most large players have optimised the flow of goods. However, this phase is also characterised by waste generated through packaging, tags, hangers and bags, as well as by a large proportion of products that never reach consumers as the unsold leftovers are thrown away.

Consumer use also has a large environmental footprint due to the water, energy and chemicals used in washing, tumble drying and ironing, as well as to microplastics shed into the environment. In fact, this is the stage where the largest environmental footprint in the life cycle of clothes is produced, as less than half of used clothes are collected for reuse or recycling when they are no longer needed, and only 1 % are recycled into new clothes, since technologies that would enable recycling clothes into virgin fibres are only starting to emerge.

Sustainability in the fashion industry

Various ways to address these issues have been proposed, including developing new business models for clothing rental, designing products in a way that would make re-use and recycling easier (circular fashion), convincing consumers to buy fewer clothes of better quality (slow fashion), and generally steering consumer behaviour towards choosing more sustainable options.

Here are some examples according to the White Paper by the European Union Parliament:

· Slow fashion. Unlike fast fashion, slow fashion is an attempt to convince consumers to buy fewer clothes of better quality and to keep them for longer. The philosophy includesreliance on trusted supply chains, small-scale production, traditional crafting techniques, using local materials and trans-seasonal garments. It calls for a change in the economic model, towards selling fewer clothes. It is however not supposed to be EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service simply a marketing stunt to sell even more clothes. As a result it could threaten the economic survival of clothes producers unless consumers are also willing to pay higher prices.

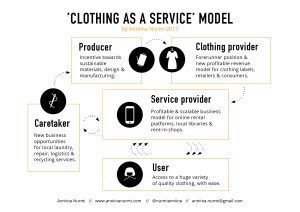

· Fashion as a service. New business models could increase the number of wears of particular items by using the principles of the sharing economy. Some brands already offer clothes as a service – leasing their clothes instead of selling them – taking their example from already well-established services of renting wedding and special occasion wear, protective clothes and newer services of renting maternity and baby clothes. Other businesses operate clothes subscription services, where consumers pay a monthly fee to rent a fixed number of garments at a time, enabling them to change their wardrobe frequently without buying new clothes (this already works well with bags and high-end fashion, but increasingly also for everyday clothes).

· Circular fashion. Like the circular economy in general, circular fashion seeks to reduce waste to a minimum and keep the materials within the consumption and production loop as long as possible. When clothes are no longer used, they should be either sold as second hand clothes or recycled. For this to be possible, products should be designed to have multiple life cycles, with recyclable materials that are tailored to the intended use, 19 timeless styles and design suitable for disassembly (modular design). Researchers and businesses are testing ways to cut fabrics to produce less waste or require fewer seams to facilitate recycling.

‘Clothing as a service’ model

In fact, there is a strong push within the industry to make every phase of production more sustainable. According to the 2018 Pulse of the Fashion Industry report, large sports apparel companies and big fashion brands are leading the way in investing in new technologies and ways of doing business, but companies in the mid-price segment are also making big improvements and even fast fashion is becoming more sustainable. There have been warnings that companies that do not change their ways may face the rising cost of materials and may have no resources to work with in the future.

However, the task is difficult because, for instance, efforts to reduce environmental impacts may result in higher prices for consumers and convincing consumers to buy fewer clothes could reduce businesses’ profits. Several studies’ recommendations include finding a more sustainable fabric mix to reduce the use of conventional cotton, improving technologies for sorting and recycling, making washing and drying more efficient, increasing energy efficiency and the use of renewable energy in technological processes, extending the longevity of clothes and improving sorting and recycling.

In 2018, the EU adopted a circular economy package that will, at the insistence of the European Parliament, for the first time ensure that textiles are collected separately in all Member States, by 2025 at the latest. The European Parliament has for years advocated promoting the use of ecological and sustainable raw materials and the re-use and recycling of clothing.

Hernaldo Turrillo is a writer and author specialised in innovation, AI, DLT, SMEs, trading, investing and new trends in technology and business. He has been working for ztudium group since 2017. He is the editor of openbusinesscouncil.org, tradersdna.com, hedgethink.com, and writes regularly for intelligenthq.com, socialmediacouncil.eu. Hernaldo was born in Spain and finally settled in London, United Kingdom, after a few years of personal growth. Hernaldo finished his Journalism bachelor degree in the University of Seville, Spain, and began working as reporter in the newspaper, Europa Sur, writing about Politics and Society. He also worked as community manager and marketing advisor in Los Barrios, Spain. Innovation, technology, politics and economy are his main interests, with special focus on new trends and ethical projects. He enjoys finding himself getting lost in words, explaining what he understands from the world and helping others. Besides a journalist, he is also a thinker and proactive in digital transformation strategies. Knowledge and ideas have no limits.