“In the beginning was the need, and the need became form, and form became expression.”

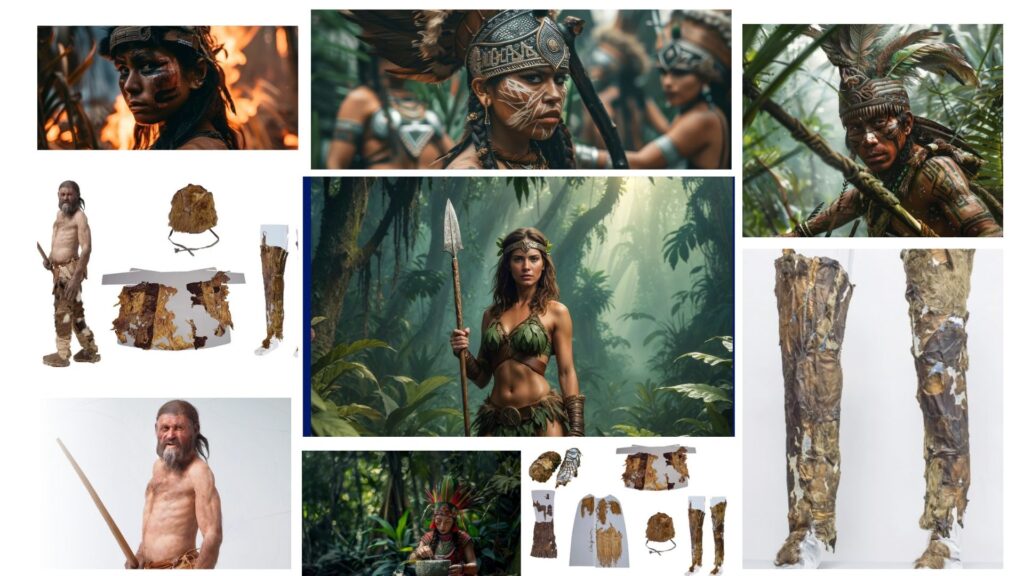

Fashion’s genesis lies not in the gilded salons of Paris, but in the primal necessity of survival. The earliest archeological evidence of fabric clothing is inferred from representations in figurines in the southern Levant dated between 11,700 and 10,500 years ago, yet the story begins far earlier.

Fashion began with the basic need for clothing, initially made from materials like animal skins, plants, and bone.

In the first breath of life, we are swaddled in fabric; in our final rest, we are shrouded in it. Between these moments lies the magnificent tapestry of human existence, woven through with threads that tell the story not merely of what we wear, but of who we are, who we have been, and who we dare to become. Fashion is an intimate part of humanity and its history is a physical and visual timeline of societal changes, evolving from the practical use of clothing in ancient times to the status symbols of ancient Mesopotamia, Rome and Egypt, and the iconic haute couture of 19th-century France.

Fashion began with the basic need for clothing, initially made from materials like animal skins, plants, and bone. Yet even in these primordial moments, humanity revealed its distinctive character—the tendency to transform necessity into artistry, function into meaning. Where other creatures developed fur, scales, or feathers through evolutionary adaptation, humans chose a different path. We became the species that creates its own plumage, that fashions its identity from the raw materials of the natural world.

Archaeological evidence reveals that our earliest ancestors, some 120,000 years ago in the caves of Morocco, were already demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of both the practical and symbolic functions of dress. They crafted garments from jackal, fox, and wildcat skins, using bone awls and stone cutting tools with a precision that speaks to the profound importance they placed upon this emerging art. These were not merely coverings against the elements; they were humanity’s first conscious attempts at self-transformation.

The invention of the eyed needle around 40,000 years ago marked a revolutionary moment in human consciousness. This tiny implement, no larger than a finger, represented a quantum leap in cognitive development. It enabled the creation of fitted garments that could follow the contours of the human body, transforming shapeless hides into sculpted forms that enhanced rather than obscured the wearer. The Cro-Magnons who mastered this technology gained warmth and a survival advantage that contributed to their success over the Neanderthals, who could only drape themselves in crudely cut skins.

Read More: edith head net worth

In ancient civilisations, clothing served as a marker of social status, as seen in Egypt and Rome. This transformation from practical necessity to social communication represented humanity’s growing sophistication in understanding the power of visual symbols. Clothing became a form of writing—a script readable by all members of society that instantly communicated one’s place in the social hierarchy, one’s occupation, religious beliefs, and cultural affiliations. The wealthy Roman’s toga, the Egyptian pharaoh’s ceremonial regalia, the Mesopotamian king’s kaunakes—each was a carefully composed statement about power, divinity, and social order.

This early recognition of fashion’s communicative power established principles that remain fundamental to human society. We understood instinctively that clothing could elevate the wearer, could transform a mortal being into something approaching the divine. The elaborate headdresses of Egyptian royalty, the purple-dyed robes of Roman emperors, the intricate jewellery of Mesopotamian nobility—all testified to humanity’s belief that through dress, one could transcend the limitations of mere flesh and approach the realm of the gods.

Fashion transcends mere utility to become humanity’s most persistent form of non-verbal communication—a language spoken through silk and cotton, expressed in cut and colour, proclaimed in every stitch that has ever graced the human form. It is the mirror in which civilisations have gazed upon themselves, the canvas upon which they have painted their dreams, fears, aspirations, and revolutions. From the cave paintings of Lascaux showing our ancestors adorned in animal skins to the digital runways of today where models stride through virtual realities, fashion remains the constant companion of human consciousness.

Each garment carries within its fibers the accumulated wisdom of countless generations who understood that to dress is to declare one’s place in the great drama of human existence.

The 20th century saw rapid evolution, with distinct styles emerging each decade, influenced by cultural movements and iconic designers. Yet this acceleration merely magnified what fashion has always been: a reflection of humanity’s restless spirit, forever seeking new forms of expression, new ways to transform the mundane act of covering the body into statements of identity, belonging, rebellion, and beauty. Each garment carries within its fibers the accumulated wisdom of countless generations who understood that to dress is not merely to cover oneself, but to declare one’s place in the great drama of human existence.

The story of fashion begins in the mists of pre-history, when humanity first awakened to the possibility that covering the body could be more than mere protection—it could be transformation. For nearly 90,000 years, anatomically modern humans lived without clothing, their naked forms moving through landscapes that would eventually be draped in the finest silks and adorned with precious metals. This extended period of nudity makes the eventual adoption of clothing all the more significant, representing not evolutionary necessity, but conscious choice.

The pre-historic development of clothing reveals humanity’s distinctive characteristic: the ability to see potential where others see only material. A Neanderthal might wrap themselves in an animal hide for warmth; a Cro-Magnon would see in that same hide the possibility for fitted garments that could follow the body’s contours, enhance its natural beauty, and proclaim the wearer’s skill and status. This difference in vision—this capacity to transform the purely functional into the aesthetically meaningful—may well have contributed to modern humanity’s eventual dominance.

Ötzi the Iceman, preserved in alpine ice for over 5,000 years, provides us with a remarkable window into pre-historic fashion sophistication. His ensemble was not a crude assemblage of animal skins but a carefully constructed outfit comprising a long-sleeved fur coat, leather leggings, a loincloth, grass-stuffed leather boots, and a fur cap. Each piece was precisely fitted, sewn with sinew, and designed for both functionality and durability. Here was pre-historic haute couture—clothing that protected whilst expressing the wearer’s understanding of tailored construction and aesthetic balance.

Ötzi’s clothes on display at the Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano

The development of the eyed needle represented a technological breakthrough comparable to the invention of the wheel or the discovery of fire. This simple tool enabled complex garment construction, allowing pre-historic peoples to create clothing that moved with the body rather than against it. The needle democratised fashion, making sophisticated dress possible for anyone with the skill to use it. It transformed clothing from simple covering to complex construction, establishing the craft traditions that would eventually evolve into the fashion industry.

More Contents:

century of change 20th century revolution 1900-2000

baroque brilliance and rococo romance 1600-1789

The Naked Truth

Current evidence indicates that anatomically modern humans were naked in pre-history for at least 90,000 years before they invented clothing. This extended period of nudity reveals humanity’s remarkable adaptability and the profound significance of clothing’s eventual adoption.

Climate As Couturier

The invention of clothing emerged from humanity’s relationship with climate change during the Pleistocene. Even in relatively mild Morocco, clothes were adopted as a way to keep warm around 120,000 years ago, coinciding with the onset of an Ice Age. Yet this was not merely survival—the invention of animal-based apparel also corresponds with the appearance of personal adornments, like shell beads, which hints that prehistoric clothing, like today’s styles, could have been about style as well as functionality.

Technological Triumph

The creation of fitted clothing required revolutionary innovations. The origin of complex, fitted clothing required the invention of fine stone knives for cutting skins into pieces, and the eyed needle for sewing. This was done by Cro-Magnons, who migrated to Europe around 35,000 years ago. In contrast, The Neanderthal occupied the same region, but became extinct in part because they could not make fitted garments; they draped themselves with crudely cut skins.

The Ötzi Revelation

Perhaps no archaeological find better illustrates prehistoric sophistication than Ötzi the Iceman, preserved in alpine ice for 5,300 years. Over his body the man wore a long-sleeved fur coat that extended nearly to his knees. The coat was sewn from many pieces of fur, with the fur on the outside. His ensemble included animal hide short boots, stitched together with hide and stuffed with grass, probably to keep his feet warm in the snow and a simple cap of thick fur.

Key Benchmarks

|

Period |

Innovation | Significance |

|

300,000 BCE |

Loss of body hair | Necessitated eventual clothing development |

| 120,000 BCE |

First leather or fur clothing |

Morocco cave evidence |

| 40,000 BCE |

Eyed needles |

Complex garment construction possible |

| 35,000 BCE |

Cro-Magnon fitted clothing |

Survival advantage over Neanderthals |

|

11,700 BCE |

Fabric clothing evidence |

Southern Levant figurines |

Article by Dinis Guarda. With Jasmeen Dugal

Dinis Guarda is an author, academic, influencer, serial entrepreneur, and leader in 4IR, AI, Fintech, digital transformation, and Blockchain. Dinis has created various companies such as Ztudium tech platform; founder of global digital platform directory businessabc.net; digital transformation platform to empower, guide and index cities citiesabc.com and fashion technology platform fashionabc.org. He is also the publisher of intelligenthq.com, hedgethink.com and tradersdna.com. He has been working with the likes of UN / UNITAR, UNESCO, European Space Agency, Davos WEF, Philips, Saxo Bank, Mastercard, Barclays, and governments all over the world.

With over two decades of experience in international business, C-level positions, and digital transformation, Dinis has worked with new tech, cryptocurrencies, driven ICOs, regulation, compliance, and legal international processes, and has created a bank, and been involved in the inception of some of the top 100 digital currencies.

He creates and helps build ventures focused on global growth, 360 digital strategies, sustainable innovation, Blockchain, Fintech, AI and new emerging business models such as ICOs / tokenomics.

Dinis is the founder/CEO of ztudium that manages blocksdna / lifesdna. These products and platforms offer multiple AI P2P, fintech, blockchain, search engine and PaaS solutions in consumer wellness healthcare and life style with a global team of experts and universities.

He is the founder of coinsdna a new swiss regulated, Swiss based, institutional grade token and cryptocurrencies blockchain exchange. He is founder of DragonBloc a blockchain, AI, Fintech fund and co-founder of Freedomee project.

Dinis is the author of various books. He has published different books such “4IR AI Blockchain Fintech IoT Reinventing a Nation”, “How Businesses and Governments can Prosper with Fintech, Blockchain and AI?”, also the bigger case study and book (400 pages) “Blockchain, AI and Crypto Economics – The Next Tsunami?” last the “Tokenomics and ICOs – How to be good at the new digital world of finance / Crypto” was launched in 2018.

Some of the companies Dinis created or has been involved have reached over 1 USD billions in valuation. Dinis has advised and was responsible for some top financial organisations, 100 cryptocurrencies worldwide and Fortune 500 companies.

Dinis is involved as a strategist, board member and advisor with the payments, lifestyle, blockchain reward community app Glance technologies, for whom he built the blockchain messaging / payment / loyalty software Blockimpact, the seminal Hyperloop Transportations project, Kora, and blockchain cybersecurity Privus.

He is listed in various global fintech, blockchain, AI, social media industry top lists as an influencer in position top 10/20 within 100 rankings: such as Top People In Blockchain | Cointelegraph https://top.cointelegraph.com/ and https://cryptoweekly.co/100/ .

Between 2014 and 2015 he was involved in creating a fabbanking.com a digital bank between Asia and Africa as Chief Commercial Officer and Marketing Officer responsible for all legal, tech and business development. Between 2009 and 2010 he was the founder of one of the world first fintech, social trading platforms tradingfloor.com for Saxo Bank.

He is a shareholder of the fintech social money transfer app Moneymailme and math edutech gamification children’s app Gozoa.

He has been a lecturer at Copenhagen Business School, Groupe INSEEC/Monaco University and other leading world universities.